INTRODUCTION

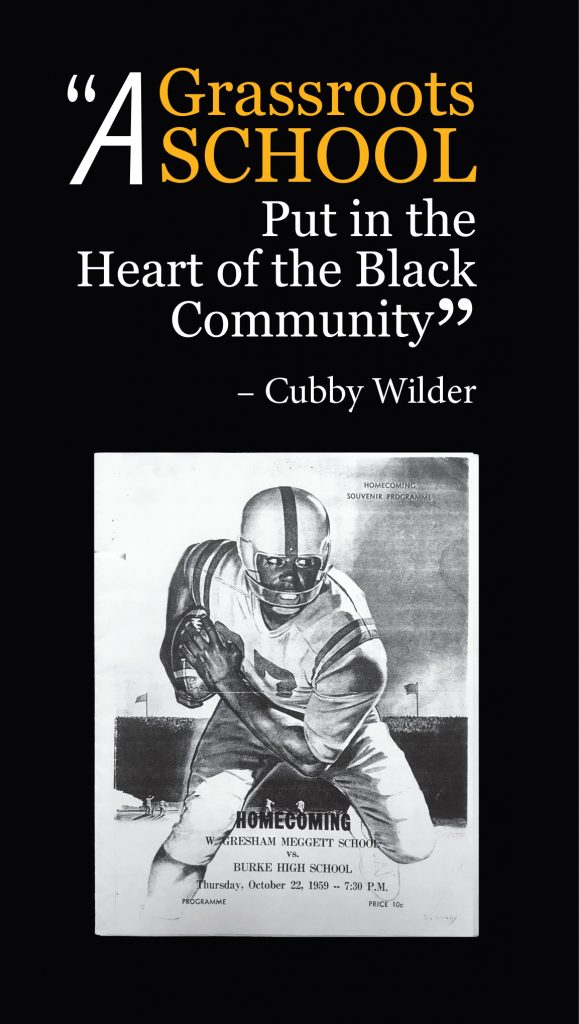

Cover of Pamphlet for Homecoming Football Game Between W. Gresham Meggett High School and Burke High School, 1959. (Provided by Anna Johnson)

Charleston County was awarded a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior and the National Park Service (NPS) in 2018 to conduct an oral history project on the lives of African American students during desegregation. The project focused specifically on oral histories collected from alumni and faculty members from the W. Gresham Meggett Elementary and High School. This historically significant school, a product of South Carolina’s equalization program, provided education for James Island’s African American children from 1953 to 1969. Named for W. Gresham Meggett (1903–1990), a former chair of the James Island School Board, it became home to the Septima P. Clark Corporate Academy vocational school in 1994 and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2016.

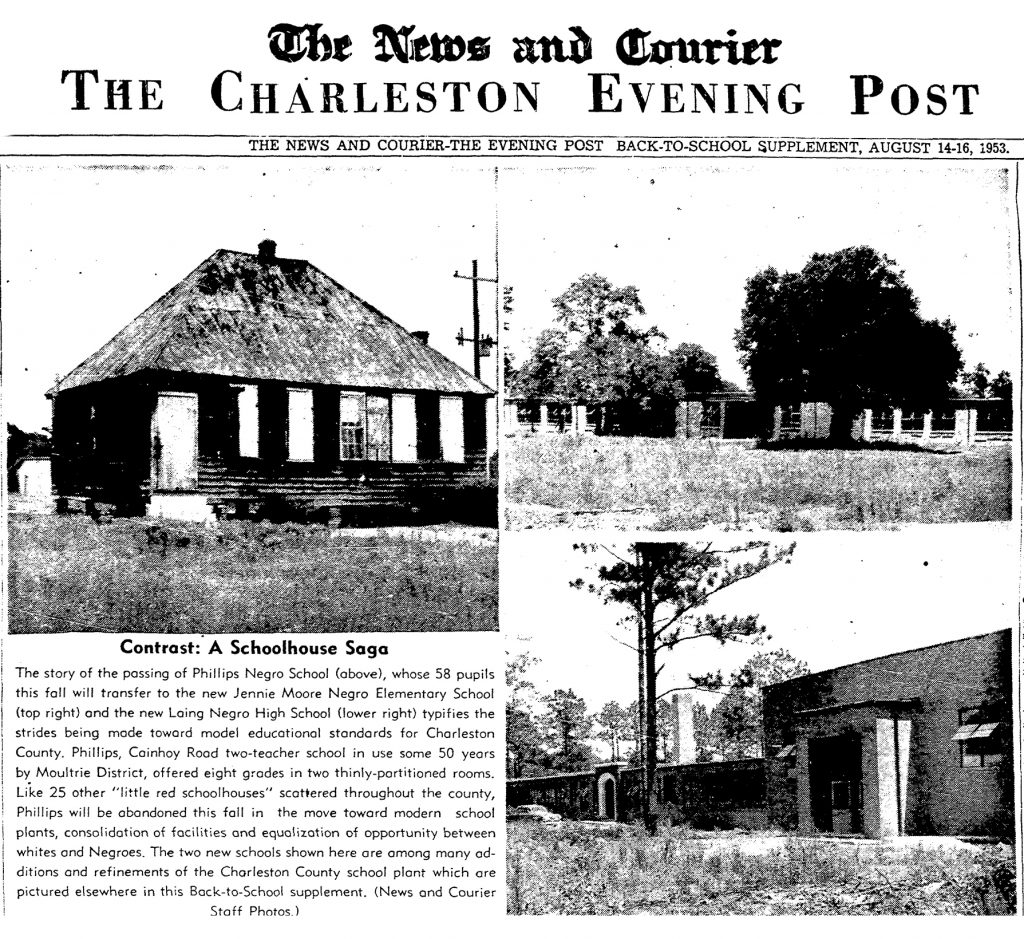

Predicated on the rationale that separate but equal facilities for white and black students in South Carolina would forestall pending federal mandates to integrate schools, South Carolina passed legislation that, among other objectives, earmarked funds for the construction and improvement of the public school system. What resulted was the statewide Equalization Program which made additions and improvements to existing schools and constructed new schools from 1951 to 1960. South Carolina had 80 African American high schools when the equalization program was enacted and an additional 145 were constructed by 1957. While the program’s early years focused on schools for African American children, the program spent more than half of the funds to improve schools for white children as well.

The newly-constructed schools were designed by architects and built by licensed contractors using modern designs and materials. The school designs were grounded in postwar educational philosophy intended to create functional and child-friendly environments. In an effort to express equality materially, all schools were constructed similarly regardless of whether it was planned for white or black children, in an urban or rural setting, or for high school or elementary students. However, while these modern schools created identity and purpose, they were not always equal and African American students went on to challenge the system in the 1960s.

Gresham Meggett Elementary and High School was a product of South Carolina’s equalization program. It was constructed in 1953 and served the community until 1969 when it became solely a vocational school. Located on James Island, with its history of cultural and physical isolation from the urban center of Charleston, W. Gresham Meggett School was one of two equalization schools built for African American children on James Island. Before the initiation of the equalization program, the African American schools on James Island – as elsewhere across the South through the mid-twentieth century – were small, underequipped, and overcrowded. Public education for most African American children, especially in rural areas, ended at the 7th grade. Meggett’s presence meant that teenagers of James Island had a viable choice to continuing their education other than the often unattainable, tuition-based and/or distant schools in the city of Charleston.

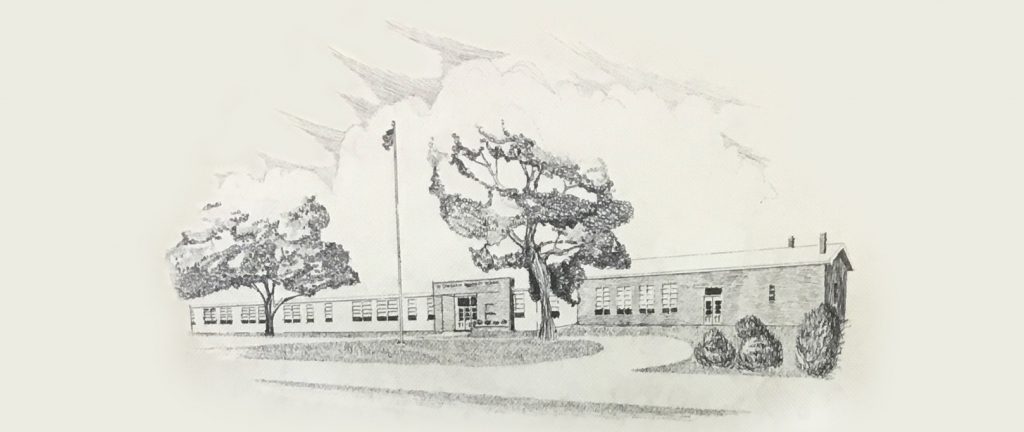

Drawing of W. Gresham Meggett Elementary and High School from a Yearbook, 1965. (Provided by Barbara Brown)

The oral histories of teachers and students from W. Gresham Meggett provide first-hand accounts of this important period of change, focusing on the rural island community and offering new perspectives on the history of rural education for African Americans between the 1940s and the 1970s. This project preserves the narratives of those who first attended the school, took part in the development of the strong educational environment it offered to the community, and went on to make history in the early years of desegregation.

Photographs of Cut Bridge, Sol Legare, and Three Trees Elementary Schools, 1956. (Provided by Anna Johnson)

EQUALIZATION SCHOOLS

Forty-four schools in Charleston County received funds for new construction, additions, renovations, and equipment. Of those schools, 20 were for white students and 24 were for African American students. Half of the white schools were new constructions while 20 of the 24 African American schools were new constructions—indicating that the existing white schools were in better condition and greater number than the existing African American schools in the county.

Jennings, Cauthren, “Contrast: A Schoolhouse Saga,” Charleston Evening Post Supplement, August 14, 1953, p.1

Five schools in District 3, James Island, received equalization funds: James Island Elementary, James Island High, and Riverland Terrace Elementary—for white students. Funds for African American schools went to Cut Bridge (Murray-LaSaine) Elementary and W. Gresham Meggett High and Elementary.

Considering that Meggett combined elementary and high schools, there were two elementary schools and one high school for each community. James Island’s schools followed the requirement that each district only operate one high school per race. All but the previously existing Riverland Terrace were newly constructed schools.

JAMES ISLAND ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

Allotted funds in 1955, the one-story school originally had 14 classrooms and two wings with long rows of windows. Architect Constantine and Constantine’s ledgers have an entry for James Island Elementary School dated 1955 for a contract worth $125,000 and a $50,000-cafeteria the following year. The ledgers also contain an entry of $10,155 for a two-classroom addition to “James Island Grade School” in 1954.

JAMES ISLAND HIGH SCHOOL

Constructed for equalization in 1953, James Island High School was originally designed as a two-winged building with eight classrooms, a multipurpose room, library, and offices by Architect A. E. Constantine. The plans, however, changed to the campus-style plan with six separate buildings connected by corridors. Many of the cost figures for James Island High are missing from the ledgers of Constantine and Constantine. While some of the plans may not have come to fruition, the architectural firm was commissioned for the following: “a proposed new building” in 1952 with additions in 1953 and 1955 totaling $56,524 each; another “new building” and eight-classroom addition in 1957; a $60,945 classroom addition the following year; a gymnasium and additional classrooms in 1961; additional classrooms in 1963; another gymnasium in 1964 costing $300,000 (noting that the cost included a gym for Meggett as well); and finally a music building in 1967.

RIVERLAND TERRACE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

Funds were approved in 1954 and 1957 for additions and renovations to Riverland Terrace completed by architect Constantine and Constantine totaled $30,299 and $10,935, respectively The elementary school was razed prior to 1971, as evidenced in historic aerial photographs.

MURRAY-LASAINE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

When Murray-LaSaine Elementary School opened in 1955 it consisted of 16 classrooms. Constantine and Constantine referred to the school as “Cut Bridge” in the ledgers since it replaced the original one-room schoolhouse. The school district commissioned the architects in 1954 for the original school at a cost of for $192,000, plus another $64,185 the following year. A $32,000 cafeteria was added in 1956, a classroom addition in 1960, and another addition for $85,000 in 1964. The school is named for Albertha Johnston Murray, former principal of Cut Bridge School, and Dr. M. Alice LaSaine, former supervisor of Black schools in Charleston County. According to Historian Rebecca Dobrasko, Murray was integral in forcing the hand of Charleston County School District into upgrading Cut Bridge School, showing the county’s reluctance to satisfy the African American teachers and parents during the equalization program.

GRESHAM MEGGETT ELEMENTARY AND HIGH SCHOOL

The fifth school to receive funds from the equalization program was W. Gresham Meggett Elementary and High School. The county intended to build a modern elementary school with the intention of consolidating several of the older, smaller, one-room schoolhouses – Cut Bridge, Sol Legare, Society Corner, and Three Trees – into Meggett. Later Cut Bridge Elementary was replaced by Murray-LaSaine Elementary instead and the remaining schools were closed and consolidated into Meggett Elementary. While first conceived as an elementary school, plans changed quickly in response to the growing number of prospective students, the proposed consolidation of schools, and the need for a high school that served only African Americans. Having a separate but equal school system was the state’s goal.

Photograph is Herbert Augustus DeCosta, Jr. (1923-2008) (College of Charleston, Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture, AMN 1084)

The firm of H. A. DeCosta won the construction bid at $157,000. Renowned for their preservation and restoration of historic properties, the DeCosta Company was one of the most active Charleston construction companies in the mid-twentieth century. The company had its origins in Benjamin Rhodes DeCosta (1867-1911), a craftsman among a set of skilled African American artisans and builders in the city of Charleston.

The H. A. DeCosta Company came into its own in the mid-twentieth century with the third- generation architect/builder Herbert Alexander DeCosta (1923-2008). Education was vital in the DeCosta family and H. A. DeCosta, Jr. attended Avery Institute, from which he graduated in 1940. He then received a degree in architectural engineering from Iowa State University in 1944 before working for the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, the predecessor to NASA during World War II.

Augustus Edison Constantine (1898-1976), Architect of W. Gresham Meggett Elementary and High School, 1921. (The Blue Print, Vol. XIV, Georgia School of Technology)

The architectural design was the work of local architect Augustus E. Constantine. Augustus Edison Constantine (1898-1976) was a prominent Charleston architect whose Neo-classical, Art Deco, Moderne, and International style buildings can still be found throughout the Charleston area. His firm is credited with designing many of Charleston County’s schools during this era of expansion including W. Gresham Meggett Elementary and High School.

The centrally located elementary school, designed as a six-room concrete block construction and built in 1951, was swiftly expanded in 1952 to accommodate the incoming high school students. The high school addition was large, accommodating “nine classrooms, a home economics room, science laboratory, library, multi-purpose room (also a cafeteria), teacher’s lounge, first aid room, reception room, principal’s office, kitchen and book storage.” Superintendent G. Creighton Frampton declared that the one-story building with its modern lighting and large green “blackboards” was “a radical departure from the old-style rural schools now in use.”

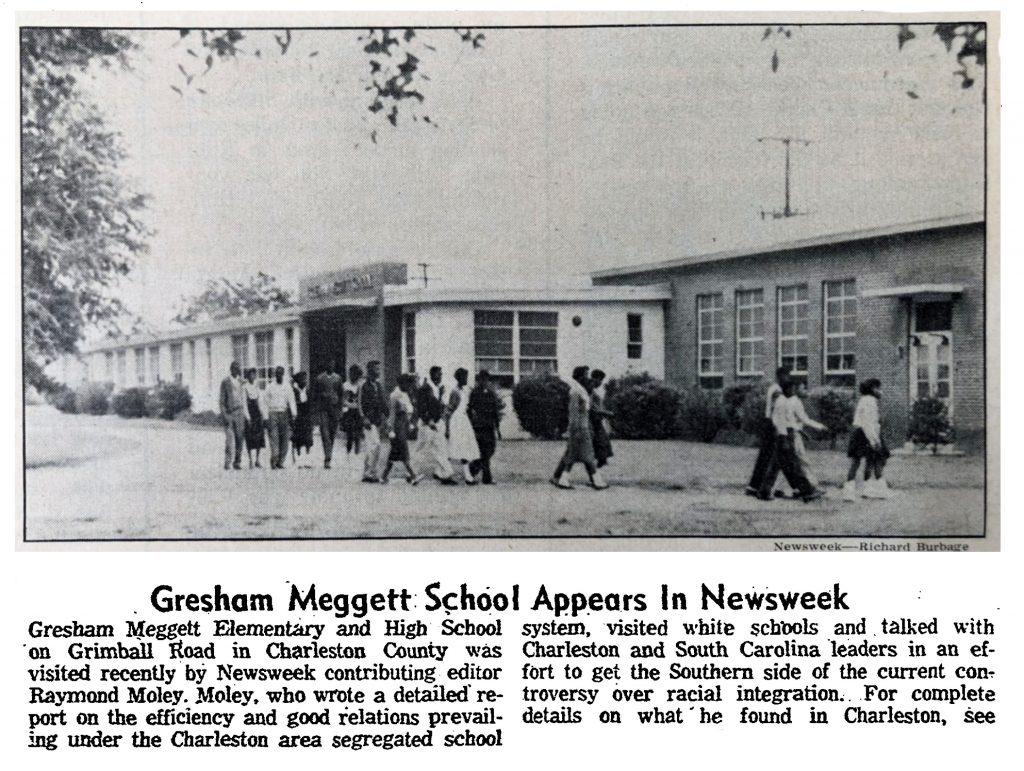

Newspaper Clipping of “Gresham Meggett School Appears in Newsweek” from the Charleston News and Courier, October 10, 1957

Equalization school buildings such as W. Gresham Meggett were designed according to popular post-World War II philosophies concerning what constituted a proper and healthy learning environment. Overall, optimal lighting and ventilation were the most important features, as well as a commitment to a one-story design thought to be more psychologically friendly to children as architects believed that “the low-lying, sprawled-out type of building, close to the ground, one story high, straight in its lines, honestly functional, is less awe-inspiring and more friendly in the eyes of the child…” This style of design did away with multi-story, classically designed facilities common for educational buildings in the previous century in urban contexts, as well as the need for stairs and fire escapes. New high schools were built as campuses, an emerging national trend.

Despite material equality in the building of African American schools, the equalization program failed to fully uphold equality as the state of South Carolina remained reluctant to provide such features as football fields to African American schools, which the state considered “not practical.”

By the close of the 1950s, only three schools served James Island’s African American children: W. Gresham Meggett High School and W. Gresham Meggett Elementary, Murray-LaSaine Elementary and King’s Highway Elementary. One year after construction, Meggett Elementary was considered over-crowded. A 1957 news article in the Charleston News and Courier noted an overall leap in enrollment on James Island but specifically cited W. Gresham Meggett Elementary School expanding from 378 students in 1953 to 416. Similarly, Meggett High School’s enrollment leaped from 186 to 271 students in 1954 while Sol Legare and Cut Bridge would have more modest gains in student populations.

To keep up with enrollment, some Meggett Elementary students were transferred to King’s Highway Elementary. The school, originally used by the white children of the community, was used by the African American community during consolidation and equalization. Transferring children to Kings Highway allowed more high school space at Gresham Meggett, which was also starting to feel the squeeze. An annex was added in 1956 supplying more classroom space and the construction of a gymnasium in 1967 also designed by architect Augustus Constantine completed the growing school which would bring African American education on James Island into the modern era when it opened in the fall of 1953.

The new and modern W. Gresham Meggett High School was positively embraced by James Island’s rural African American community, who seized the opportunity for their children to finally receive a higher education. That success brought both admiration and unease. The admiration was well deserved as dedicated professional teachers, small class sizes, and most importantly, children ready to learn with strong parental support came together to form what was a transformational educational environment. Many children now looked beyond the farm for their future careers and a college education was now achievable for some. Yearbooks show the Meggett’s students quickly learned 1950s American high school culture and participated in it to the extent possible under segregation. Photographs feature young Black scholars, bricklayers, prom nights, homecoming weekend, sports events, teams and coaches, choir, clubs, awards and who got a school letter. Until its closing in 1969 at the beginning of integration, W. Gresham Meggett High School and its community turned out a graduating class of young Black men and women with expectations.